by Brandon Rhodes

• Home

A New Driver for the Original Twiddler

The practical take-away from this post

is that if you’re ever trying to debug serial communications

with a device that — against all tradition —

only transmits when the Data Terminal Ready line is clear

(devices should normally do the opposite:

transmit only when Data Terminal Ready is set),

then never run stty on the serial port

to double-check your settings.

Why?

Because stty turns Data Terminal Ready back on.

Without even asking you!

So the device will never communicate with you,

and you may very nearly conclude that your device is broken

before you happen to remove the stty call

and see the device finally work.

So that’s the take-away.

But the full story is a bit longer.

Typing with one hand

After a recent marathon two-day coding session

left my wrists aching slightly,

I decided to look for an alternative keyboard

for tasks like browsing documentation and catching up on email.

While I will always want the bandwidth of a full two-handed keyboard

when composing text,

I decided to try out my old Twiddler keyboard for browsing,

since Gmail shortcuts

should be easy enough to type with one hand.

The Twiddler keyboard uses chords

to allow a single hand

to produce all the keystrokes possible on a typical keyboard.

You press a combination of buttons, instead of just one,

to type a single letter or symbol.

Normal keyboards issue a letter or symbol

the moment you put a key down.

But because a chording keyboard doesn’t know the complete chord

until all your fingers are down,

it waits until the moment you finish and lift a finger back up

to type the character corresponding to that chord.

I disliked the Twiddler’s native keyboard mapping,

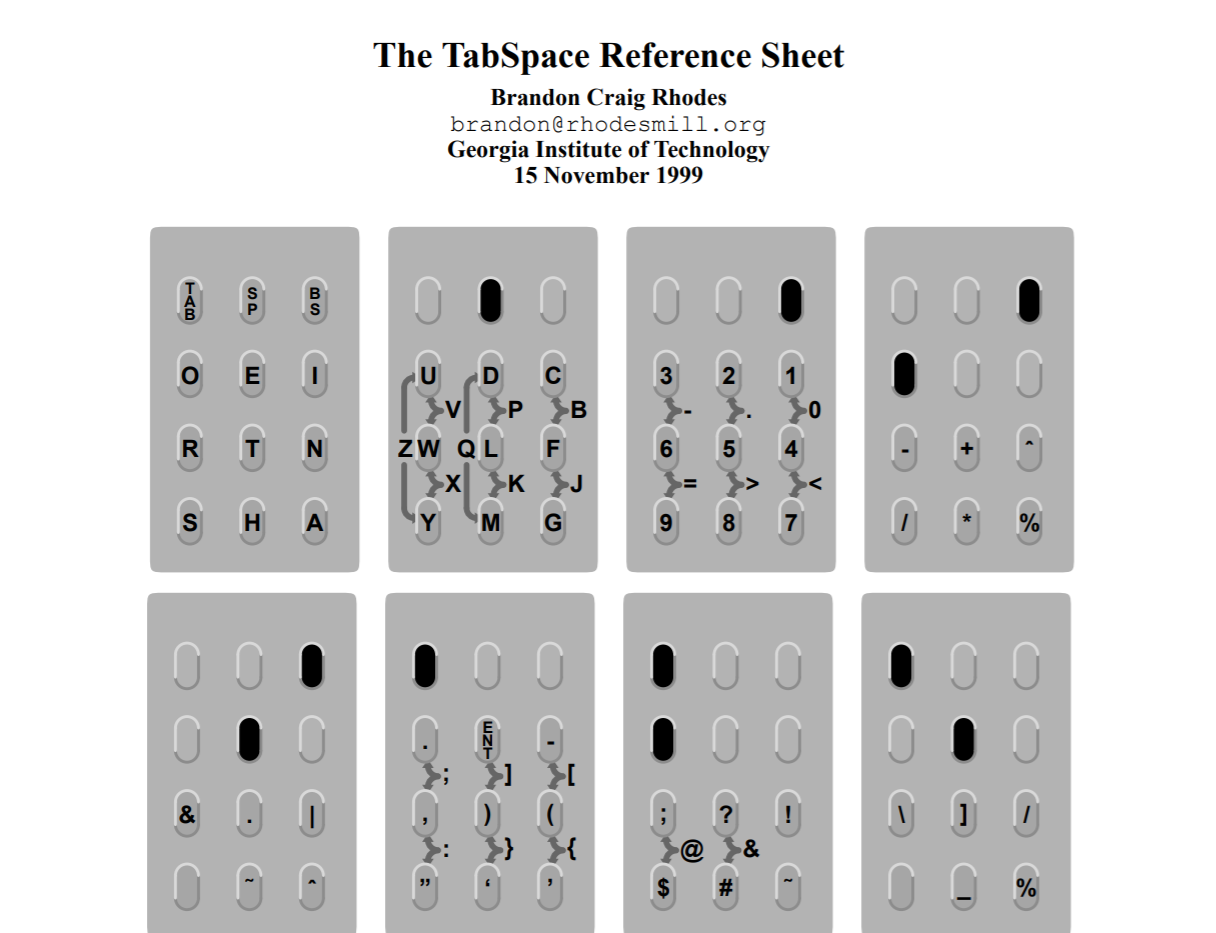

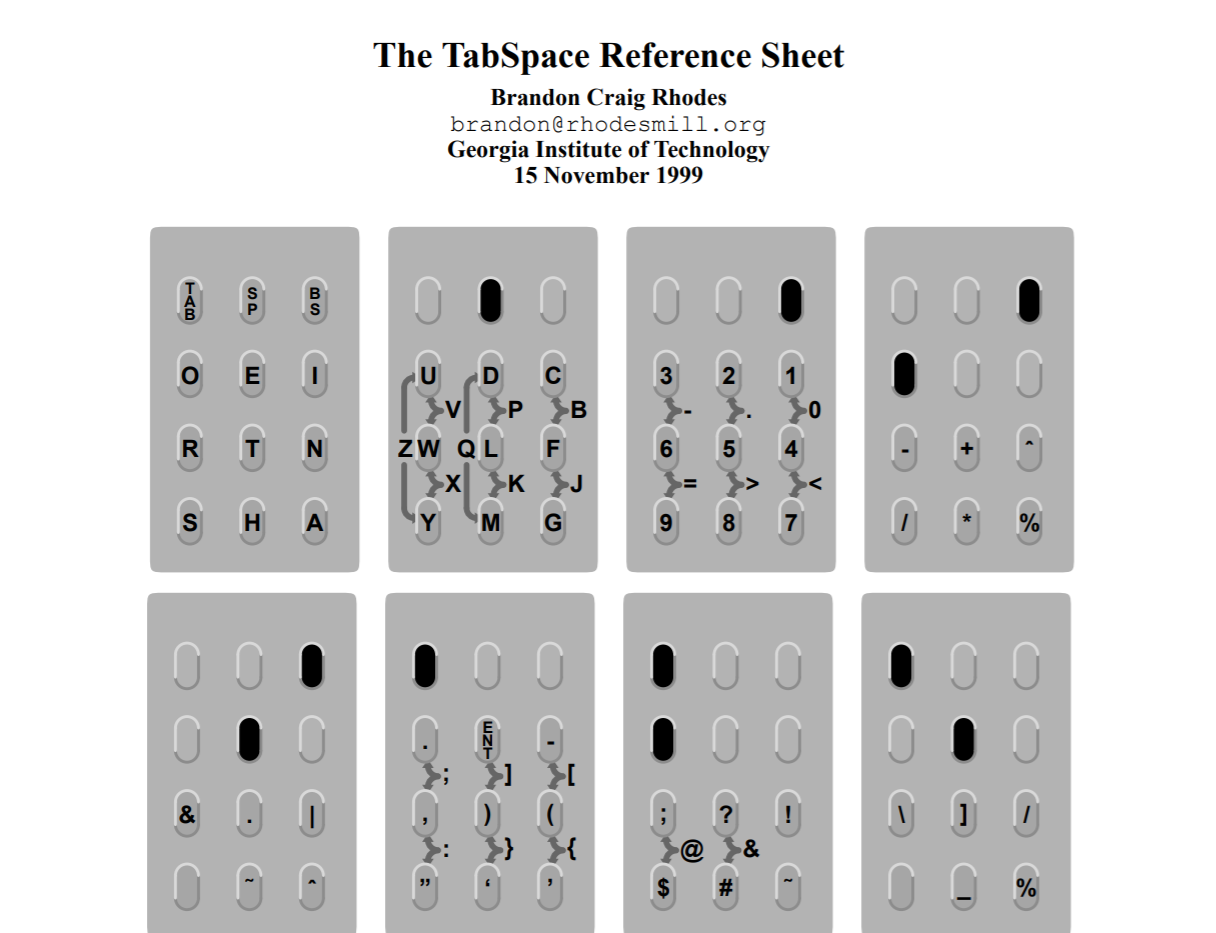

so I came up with my own mapping that I named “TabSpace”

and that’s still available from my old projects page:

It may surprise you

to learn that even though I’m the author

of a custom Twiddler keyboard map renowned for its efficiency,

I never wound up using the Twiddler much.

I bought it in grad school

when I was briefly interested in wearable computing —

back when that meant running Emacs in a glasses-mounted display

powered by a computer in an over-the-shoulder satchel.

I wound up interested in other forms of mobile computing

after my workplace issued me

a Palm V.

I realized that I preferred a mobile experience

that could be stashed away in a pocket

to a device that would be constantly intruding in my line of sight.

So many cables

So pulling the old Twiddler back out for browsing email

seemed like a great chance to finally use the device.

The first surprise was the reminder that its cables

are quite a bit different from those of a modern keyboard:

It took a few tries to remember why the Twiddler needs two connectors.

The Twiddler design constraints seem to have been:

- They wanted to support custom user-defined keymaps.

- But if the Twiddler itself

had implemented the mapping between typed chords

and the resulting text,

then it would have required both onboard RAM —

making its electronics more expensive and complex —

as well as an incoming data stream

over which the custom keymap could be uploaded,

adding complexity to both the protocol and software.

- They therefore decided that the Twiddler itself

would only transmit the raw chords that the user pressed.

Translation from chords to keystrokes

would happen in a driver on the computer itself.

- This meant that the Twiddler could not send its input

to the PS/2 keyboard port.

The operating system would have interpreted the data

as real keystrokes.

- Which incoming data port were operating systems of the late 1990s

agnostic about?

The serial port!

Desktop operating systems tended to ignore it by default,

so a Twiddler driver could interpret the data as it pleased.

- The Twiddler might thus have been designed

purely for the serial port.

But how would it then have been powered?

One possibility would have been its own A/C power supply.

Another would have been a compartment for batteries.

Instead, the designers opted to use the same power supply

that normal keyboards use:

the 5 volts offered at the PS/2 port.

Thus the Twiddler comes with a double cord,

offering a serial connector that communicates but provides no power,

and a PS/2 keyboard DIN connector that accepts power

but performs no communication!

- So that users could also connect a traditional keyboard,

the Twiddler added a female PS/2 connector to the end of the cord

where — once the device has grabbed the 5 volts it needs —

a normal keyboard can take power from and provide data to the port.

I wasn’t able to connect the Twiddler to my laptop.

While I found a small PS/2-to-USB converter in a drawer,

that left the Twiddler without any way to communicate.

To both give it power and also receive data,

I had to move over to my Linux desktop —

apparently the last computer in the entire house with a serial port.

This means I’ll stand at its monitor

to check my email instead of sitting in the easy chair.

While I’m not as comfortable or productive

when I try writing code at a standing desk,

it should be fine for reading email.

Driver archaeology

After several increasingly obscure Google searches —

it always amazes me how little of the late 1990s

seems to survive in searchable form —

I found two extant open source drivers for the original Twiddler.

The old general purpose mouse (gpm) daemon

has not only survived the long years

but features a

sporadically active GitHub repository

and includes the Twiddler among the serial mice it supports.

However, it appears that gpm

can only broadcast mouse events (motion and mouse button clicks)

to the X Windows system — not keystrokes,

which it can only offer to the bare Linux console.

This of course makes perfect sense

for a daemon that’s really designed as a mouse driver,

not a keyboard driver.

A quick experiment suggested that gpm doesn’t know to select the correct

baud rate for the Twiddler

(though, confusingly enough, gpm does mention the correct baud rate in a source code comment),

so I wasn’t able to get gpm working with the Twiddler

even for typing at the Linux console.

But there is an alternative to gpm.

Happily, it appears that a single lone copy still exists

of the open-source Linux drivers I remember using originally,

though they required a bit more searching:

the old MIT Wearable Computing site’s

Keyboards page

offers a copy of Jeff Levine’s

twid-linux.tar.gz

driver.

Even after all of these years,

I was able to coax it into compiling on modern Linux —

but the result was only that my mouse

began to jitter around on my screen

without the Twiddler appearing to be in control.

A quick strace revealed that the driver

was at least reading data successfully from the serial port,

but it was evidently not making sense to the driver.

Was my old device simply broken,

and it was in vain that I had kept it carefully in its box all these years?

Or was the driver not communicating correctly?

It was clearly time to step in with some simple Python code

to bypass the intricacies of the old drivers

and see if reliable communication could be established.

Establishing communication

The worst kind of debugging

is where you start in a broken state

and have no idea whether one tweak or a dozen tweaks

stand between you and a solution —

and you have no way of knowing whether any particular tweak you make

is moving you closer to the goal or farther away.

But I did have one glimmering source of hope

as I stepped my Python code

through many permutations of baud rate, stop bits,

and other serial port and TTY settings:

I was heartened by the fact that I could still see data flowing with strace

whenever I powered back up the old legacy drivers.

In fact I kept doing that, every half hour or so,

just to convince myself the device wasn’t broken and silent.

My old Twiddler — I had to keep reminding myself —

could, somehow, still be induced to send bits.

The problem was that when I tried establishing

the same communications settings in my own script

as had been used in the original drivers —

even being careful to drop DTR, exactly like the original driver does

(the “Data Terminal Ready” serial line,

which would normally be set if the computer were ready to receive)

— I still saw no data.

What was going on?

The answer is that my code,

by this point in its development and debugging,

looked roughly like:

# Set up terminal settings.

f = open('/dev/ttyS0', 'r+b', buffering=0)

...

# Print the settings to the screen to double-check.

os.system('stty -a < /dev/ttyS0')

# Try reading from the port.

...It turns out? I was betrayed by stty -a!

I thought it would merely read the state of the serial port

without changing it,

but instead it was undoing my careful work

of setting DTR to a non-standard value

and was turning it back on instead.

It was one of those stunning Heisenberg moments

when a tool you had thought was a clear lens for observation

turns out to itself have been affecting the state of your experiment!

To get the driver working:

- I stopped using stty for any debugging or verification

of my serial port settings.

- I had to abandon the original driver’s maneuver

of setting the baud rate first to 2400 baud

and then to zero baud (!).

Apparently, this would induce a 1990s Linux serial port

to actually remain at 2400 baud

while turning off the DTR line.

On modern kernels?

It ruins the 2400 baud rate setting —

which is why the 1990s drivers were seeing nonsense data

and making the mouse cursor jitter all over the screen.

- I instead used the modern ioctl(2) call TIOCMBIC

with the parameter TIOCM_DTR

to cleanly turn off (“clear”) the Data Terminal Ready line

without affecting the baud rate.

Only once all of these settings were in place

did the serial line light up

and the Twiddler started sending coherent data,

in the format promised by the comments of the various drivers —

five-byte packets each giving the state of each button

and the x- and y-orientation of the device

for driving a mouse position.

My repository

For the sake of digital preservation,

I’ve checked in to GitHub

not only the Python code of my own driver

but the original C-language driver by Jeff Levine:

https://github.com/brandon-rhodes/twiddler-1-driver

I’m happy to have written a new driver

that no longer needs root permission to operation,

that works with modern kernels,

and involves no compilation step.

In case anyone else with one of these old devices

should stumble by the repository,

I hope it works for you as well!

©2021