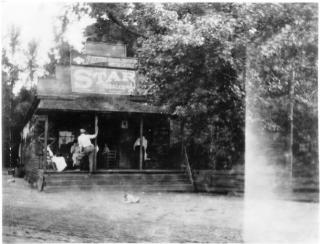

The mill commissary survived as a general store (1916).

The mill commissary survived as a general store (1916).

Greatgrandfather must have founded the mill; at the earliest memory of persons now living it had been there forever. During father’s boyhood it was an impressive industrial operation.

Virgin long-leaf pine timber was cut and transported to the mill as logs, which would sometimes square up 28 × 28 inches, sometimes 36 feet long! There was machinery for primary sawing. There was a dry kiln for lumber struck while squaring the huge “export” timbers, and cut from smaller logs. There were gang saws for ripping lumber, and a planer for manufacturing finished lumber and molding.

Two boilers supplied steam, and the mill machinery was driven off line shafts that were turned by a reciprocating steam engine that must have produced about 100 horsepower.

Appendages to the mill were a commissary (general store), a blacksmith shop, a grist mill and a cotton gin. The last two were operated only in season.

The foregoing, along with 7000 acres of timber, is a sizable collection of capital in any age. How the complex was financed I have no idea; if there were debts, no one now living seems aware of them.

Huge squared timbers were sold for export at Pensacola; lumber for the domestic market was sold locally, and shipped by rail from Rhodes Station on the A&F Division of the L&N Railroad. (This division was not opened until about 1898; before that, lumber must have been carried to Georgiana for rail loading. The line from Mobile to Montgomery, through Georgiana, was there during the Civil War, and was one link in the first massive movement of troops by rail: the removal of the Confederate Army from Mississippi, and its transferral to Chattanooga.) A sizable community was supported by the mill.

Accompanying sketches show the layout of the several mill buildings, the machinery layout in the mill itself, and a rough map of the community. Only a few of the buildings are shown—those associated with the mill and the family. There were more. The community was not a pretty one by present-day subdivision standards. The structures were sturdy; there was an abundance of lumber and labor. The architecture was “Sawmill American.” Buildings were put where they were needed. The environmental impact of the whole operation was that the virgin timber was cut. That is all. There is no trace, today, of all the activity. Only one building stands, Wesley Chapel Church. The timber has regrown and been cut again several times. The burial grounds survive.

The mill pond was the terminus of a trunk line for transporting logs. Persimmon creek was dammed up so that it formed a pond whose slews reached far into the forest. The dam itself was of wood, and the mill straddled the creek over the dam. Originally water power drove the mill; Grandpa said the flow decreased until it was necessary to put in steam. This seems unlikely; what more likely occurred is that from year to year, more and more machinery was added to the line shafts, and this demanded more and more water through the turbine, and indeed, the mill pond level would not keep up.

After steam was installed, only the grist mill ran on water power. I saw a millstone and the turbine shaft and blades to that mill lying in the yard of the “home place” in the early 1950’s. The millstones were there in November 1989, but we could not find the turbine runner.

Logs were cut, not by chain saws, but by axes and cross cut saws and men. They were dragged, or carried on log wheels, by oxen to the water, and towed to the mill pond. The pond was one “log warehouse” from which stock was drawn to feed the main saw. A chain with dogs on it would pull a log up onto a dock behind the mill at the level of the saw. The carriage would be backed out onto the dock and a log would be rolled with cant hooks onto the carriage. A cable or chain, under the control of the sawyer, and driven from the mill’s power train, rolled the carriage past the saw. The carriage wheels ran on inverted-‘V’ tracks. In many mills there was a cut-off saw, a swinging cut-off blade, that cut the log to length before work was started by the main saw. Father has said there was no cut-off saw at Rhodes Mill. (There was a swing saw for cutting butts to length for the shingle mill.) Logs must have been cut to length as they were felled, or by hand, before or after they were set onto the carriage.

Head blocks clamped the log to the carriage.

After a slab or board was ripped off, and the carriage returned to a position ahead of the main saw, the log would be indexed over for the next cut. In this, and all subsequent operations, the sawyer’s judgment determined how many boards were cut and how thick each one was. An on-line computer—the sawyer’s brain—weighed many things to make the decisions. Among the considerations were the board sizes needed to fill an order or maintain inventory, the market for export timber (the core of the log was usually squared up for this), the myriad variations in the wood, itself, and given this particular log, what cuts would yield the greatest value.

The sawyer was a very important man.

When time came to turn the log ninety degrees on the carriage, the headblocks were released, and a steam driven piston drove up a toothed bar, called a nigger, which snagged the log, or timber, and flipped it over. I do not know the origin of the word. (In smaller sawmilling operations, the logs were turned on the carriage by men with cant hooks or peaveys, the number of men dictated by the size of the log. This is true today on portable sawmills.)

Boards peeled off of the timber by the main saw fell onto live rollers that carried them to the track where they were loaded onto the dry kiln cars and stacked, so that hot air could circulate around them individually and remove their moisture. (As well as removing moisture, the high temperature of the kiln alters the structure of the wood so that it is more stable; it comes and goes less with humidity.)

When only an export timber was left, it was turned off the carriage onto other rollers and transported out to a shed on the creek bank just below the dam. It was rolled sideways into the creek. It floated downstream to where these timbers were collected into rafts for floating to Pensacola when floodwater came in the spring. All year these timbers, and the rafts they made, were collected along the creek.

On a photograph of the mill, and on my sketch derived from it, there is a board missing below a window that is over the creek. Father recalls that this board was knocked off when one of the timbers went off its rollers into the creek, downstream end first, instead of sideways. The end snagged the bottom, and the upstream end fell off, striking the mill wall as it did so. The shed covering this timber dumping shelf has its roof fallen down in the photograph. This followed decay and neglect during the ten or fifteen years after the mill was abandoned and before the photograph was made.

There was not the romance of a log drive to the mill like one reads of in Maine and Michigan; dammed-up Persimmon creek was a docile transport artery for logs above the dam, but the running of rafts of squared timber to tidewater deserves some romantic literature. It was dangerous enough. The men who ran the rafts must have developed traditions and maybe folk heroes, but most amazing is that it was done at all. Those timber rafts and their handling embodied “folk engineering,” tuned to the medium to be worked—heavy timbers and a flooded stream—that evokes admiration as does an outrigger sailing canoe in the South Seas.

Each timber must have weighed three to seven thousand pounds. They were, typically, 26″ × 28″, and 28 feet long. (Their length was limited, not only by the trees from which they were cut, but by the length of the log carriage track in the mill. The carriage track had to be nominally twice the length of the longest timber squared. I do not know the track length in Rhodes’ Mill.)

Two relatively short timbers would be floated to form a ‘V’, pointing downstream; the apex would be lap-jointed and pegged with split oak pegs driven into auger holes. Upstream from the ‘V’ parallel timbers would be similarly joined, stringing back behind the ‘V’. When long enough, the area that was enclosed, except for the upstream side, would be filled with floating timbers. Finally, a timber would be pegged across to close the back end of the raft, and several four-by-eights would be laid across the raft. They would be pegged to the outer longitudinal timbers, and sawed off just outside. The raft was not rigid, but its width was well defined by this last operation.

A hut built of scrap lumber protected the supplies, and possibly crew members, in inclement weather. A hearth of clay would be shovelled onto the raft near the hut for a fire for cooking, for warmth at night, and for drying out water-soaked clothing and bedding.

A pair of pegs at the bow were fulcrums for a twenty-foot-long sweep oar, made of a four-by-six, with a slotted end, into which a blade was pegged. This sweep, deployed to the front, would stabilize the raft when it entered fast water in shoals, and the raft was moving slower than the water. Poles must have sufficed when the fast moving raft entered relatively still water below shoals, as I have not heard of protruding pegs at the rear.

The pointed front end served no hydrodynamic purpose; it could have been installed first on the general notion that water craft are pointed at the front. A raft’s forward motion, relative to the water, was seldom fast enough for the outline shape to matter much. It did, however, serve to sweep debris to the side, and to deflect the raft sideways if a snag or bridge pillar were contacted. But the forward deployed sweep oar was absolutely necessary to prevent broaching when the raft entered fast water.

Father thought the rafts were typically eighteen to twenty feet wide, and of the proportions shown in the sketch. This would make them sixty to eighty feet long. It is difficult to imagine maneuvering such a craft down a flooded creek with brush crowding its banks. However, if he were wrong by a factor of two, and the rafts were only ten feet wide, the operation was still an impressive one. I have asked Aunt Bessie about the size of the rafts recently (1984-85). Once she pointed out the width on the floor of the building we were in. It was about twenty feet. However, she remembered the proportions that would make them thirty or forty feet long. I expect Father’s recollection is the better. He was older, and interested in the operation when he last saw them. He was allowed to ride a raft over the stretch before the creek entered the river.

After construction, the raft would then be poled downstream and tied up in a long string of similar rafts. All summer the string would grow, and on through fall and winter, until spring rains flooded the creek.

This string of timber rafts represented an enormous inventory; how was it financed? Could the domestic business carry everything for nine or ten months while millions of feet of timber were rafted up for the spring shipment? If so, why was not the pay-off big enough, when spring came, to establish a family fortune that might still be intact? Necessity bred some amazing credit structures in the South following the Civil War. Most of the people were farmers, and up until the 1930’s farmers had year-long credit until their crops came in, lots of it carried on open accounts. Those ten-month tie-ups of inventory may have seemed natural enough to Great Grandfather and to Grandpa, who lived in a land of farmers, all with year-long credit lines.

Finally spring would come, and the creek would rise. It would rise until it would flow smoothly over the “lower dam,” a mile and a half downstream, that Uncle Dan operated. One by one (to spread the risk? or was the rate limited only by the rate crews could be readied?) the rafts would move out into the stream with a crew of three or four men. They poled it to keep it in the stream, and moving as fast as possible. Two pegs at the ‘V’ in front would take a big sweep oar that stabilized the raft in fast water; such a massive craft would come up to water speed only slowly, and when the raft moved from slower to faster water the sweep had to be put out to prevent the raft broaching cross-ways to the current.

Women would wait on a bridge downstream, each to see if her man was on the crew going down. If so, she would pass his provisions to him as he passed. That is how I heard it told. Undoubtedly, provisions were put on board, along with rope, tools and other supplies, before launching. What the ladies probably passed was a last home cooked meal and a fond goodbye.

Sometimes a raft would wreck in rapids, and the timber would be lost. What became of the men?

At night they would tie up. A crewman would leap ashore with a manila cable, wind it around a tree to snub the raft. When the cable end came round he would run with it downstream to another tree.

One man got his arm between the cable and a tree; the flesh was stripped to the bone. Uncle Marion Rhodes’ son, Tracy, was injured running timber, and walked all bent over. He was in the hut on a timber raft when something demolished the hut. Maybe the raft ran under an overhanging log, or a low bridge. In any event, he is said to have opposed the hut’s coming down on him with his feet, while lying on his back, but was crushed in his bent position. (Stacy later ran a pool room in Tampa.)

Persimmon Creek enters the Sepulga river, the Sepulga joins the Conecuh, then the Escambia, and the Escambia flows to tidewater northeast of Pensacola. Father (under fifteen years of age) was allowed to ride the rafts down the creek, but never down the rivers. The dangers of the river must have been great, indeed.

Grandpa and his brothers and half-brothers would ride to Pensacola, however, sell the timber, and return by train. A tug (steam launch?) would tow the raft from the head of the bay to the market where the timber was sold for export, to England and Germany, I suspect. Thousands of those timbers went out late in the nineteenth century with NMRM&M CO branded on their ends. (For Newton M. Rhodes Mill & Mercantile Co.)

At the market the timber was paid for on the spot in silver—silver dollars. Grandpa and his brother once sold their rafts and were walking on the sidewalk in Pensacola, each with two sacks of silver dollars across a shoulder, one sack in front, one behind. I guess they were headed for the bank. Now, Pensacola is a hilly town, as you can see today. It is, thus, not unlikely that there was considerable slope to the sidewalk, where, with a mighty CLANG, Grandpa’s front sack split, and spilled dollars over the pavement.

The two men scrambled; bystanders helped, and in the end only two or three dollars were missing. But one dollar that was in sight was rolling away, away down the sidewalk. Grandpa chased it; it rolled between the ankles of a briskly walking lady, and settled down to rolling at her speed. Grandpa dogged his dollar, running forward a few steps, looking, then running forward again. But Grandpa would not—certainly not—reach under the lady’s skirts for it. Down the block walked lady; behind her Grandpa cavorted, most strangely, it must have seemed to people across the street; finally, the block’s end came. The lady stepped into the gutter; the cartwheel spun, then lay on its side; lady marched on across the street. I do not know whether heads or tails were up.

Lumber from the dry kiln was moved out on its cars. Cars were unloaded, and the lumber set onto live rollers that carried it back to the mill. Gang saws ripped the boards to the several standard widths. Again, there was a sawyer; he would eye the approaching board, and set his saws by setting a lever for each saw into a selected notch. When that board had been ripped into several pieces of standard width, he would reset the saws’ positions to best rip the next board.

The ripped, rough lumber would be sorted onto wagons, and the loaded wagons would carry it to the planer. The planer dressed four sides of the lumber, and molded it if the product was tongue-and-groove flooring or ceiling. (Panelling did not connote tongue-and-groove panelling, as it does now. Sometimes walls were finished with tongue and grove beaded ceiling, however; wainscots were often so treated.)

The planing or molding knives had to be changed or adjusted for each size and type of lumber, but when it was running the planer only had to be fed. The output was graded and either loaded for hauling or stacked in the stock shed.

Father fed the planer when he was ten or twelve years old; I have the impression that he did not set up the machine. The end of a countershaft that transferred power to the planer projected into the gangway where one stood to feed the planer. Everyone banged his knees or shins on it; no one had his overalls wind up on the rotating shaft. Nobody, planer feeder or foreman or anybody else called the blacksmith or millwright to cut off the shaft.

Father was feeding the planer, just inside the window, when the timber knocked the board off the mill front.

Cants, or butts, are short lengths of timber that were cut from logs too short for export timber, or were trimmed from longer logs to make them fit the carriage. They were sawn into shingles on a shingle saw. This was a horizontal circular saw, with a carriage for the butt that moved parallel to the plane of the saw. After each cut the carriage would index down at one end, this end this time, at the other end after the next cut. It dropped the thickness of the saw cut plus the thickness of the butt end of a shingle. Shingles, as they were cut, dropped away below.

When a butt was a big one, the operator would steady it on the carriage until it had worked down some.

Tom Cox wanted to be an intellectual, but he was hampered by not knowing how to read or write. He was guiding a butt while contemplating some principle of philosophy, and failed to remove his hand as the top of the butt worked down toward the saw. He was gazing across the mill, deep in inattention, when—he screamed; he clasped the erstwhile steadying hand in his other hand; he sped through the mill and across the yard, screaming he had cut off his hand.

Uncle Jule, I believe, caught up with him, steadied him, said, “Let’s see it, Tom, I don’t see any blood.”

After persuasion, during which time all hands gathered around, Cox released his injured hand; the injury was the trimming of one of his—always long—fingernails.

Cox always carried a pencil behind his ear and a time book in his hip pocket.

He would walk up to a group of men in a discussion, listen for a few sentences, then end the discussion with an authoritative pronouncement. One such pronouncement was, “New Orleans, Mississippi is due west of here.”

The Cox family lived in one of the mill houses, the one that joined Grandpa’s homestead. The Cox children would swipe Grandma’s hens’ eggs off their nests.

I do not know when the mill was started. In the 1850 Census, Greatgrandfather is listed as a cabnet (sic) maker, and some $12,000 worth of personal property is his. This is a large amount. Possibly he owned machinery for his cabinet business, and possibly a mill for that enterprise preceded the sawmill, maybe at the same location. I cannot date the start of the sawmill, nor the lumbering operation.

A sepia photo dated (in ink) 1897 shows a very neat gabled structure from the mill pond side. Greatgrandfather and some others, including Uncle Jule, are standing on a sturdy, well constructed dock that extended the length of the mill. A log is on a ramp from the pond to the dock. This was when the mill was powered by water. No boilers or smokestacks are to be seen. The log carriage track must have extended out onto the dock; the carriage itself is not visible in the photo.

Father asserted that the building had two gabled roofs when he worked there, and I have so sketched it. This suggests that the mill building may have been doubled in size sometime after 1897, but whether the extension of the building was over the mill pond or downstream is not evident. My guess is that the addition was upstream. Neither photo I have of the mill in ruins shows enough to clearly confirm the two gables.

The mill was powered by water until about 1900. Then steam was installed. The mill expansion was probably coincident with the installation of steam.

Persimmon Creek was the highway for arriving logs and departing lumber,

and provided power for the mill before the late conversion to steam (1916).

Persimmon Creek was the highway for arriving logs and departing lumber,

and provided power for the mill before the late conversion to steam (1916).

Water power from swampy Persimmon Creek is hard to envision, although “Persimmon Creek Swamp,” proper, is below the site of the dam. Upstream there is a region of low hills, and the mill pond backed water into the ravines between them. The dam under the mill was built of wood, but there were earth levees to the northwest. Somewhere to the northwest were flood gates, a spillway and a fish trap. Rudiments of the levee were visible when I visited the site in the late ’60’s, when I located the sill of the gin mill dam just north of the present highway.

The principal water power came from a low-head water turbine, some five or six feet across, and a foot and a half high. Gates around the sides controlled flow into the turbine, and the several gates were opened or closed by turning a shaft by a handwheel in the mill, above. Water discharged under the turbine. The turbine was in a well adjacent to the dam; the wooden well protected it from debris.

In the last half of the nineteenth century many such turbines were available “off-the-shelf.” This does not seem to be generally known, as there is a good deal of fanfare whenever an “industrial archeologist” uncovers one. They were available in various sizes, various designs. One series of low head turbines was developed at South Hadley, Massachusetts, in connection with the mills there at the falls of the Connecticut River.

The turbine powered the main saw, the gang saws, and miscellaneous machinery, but the planing machine had its own source of power. It was powered by a mill-built vertical-shaft water wheel. A wooden nozzle sent a stream against paddles of wooden boards. Efficiency must have been very low. When a log got into that wheel’s well and damaged it, a millwright made a new one. However, it turned fast enough that no great RPM conversion was required to drive the high speed knives of the planer. It is easy to imagine that if the planer were added after the sawmill was going, and this homemade turbine was constructed to power it, that this demand on the water supply may have ended in the decision to install steam.

It could be that this train of events led to the demise of the enterprise. Going to steam was a sizable capital investment, and maintaining the steam plant increased the cost of running the mill. It was just six years after steam was installed that Grandpa left. Greatgrandfather was dead. By that time his brothers had other interests, except Uncle Jule, who stayed on and ran the grist mill. (Uncle Newt and Uncle Dan had a store in Georgiana; Uncle Marion was in Greenville; Uncle Dave had disappeared.)

Father remembered the conversion to steam sometime around 1900. It was a great event for him, but maybe it was the beginning of the end. Two boilers were erected northwest of the mill, and a shed was built to protect them and the firemen. Two boilers were probably common practice, as their feed water was creek water, and they had to be cleaned fairly frequently. One boiler could probably handle most of the requirements. A one-cylinder, double-acting steam engine produced up to about 100 HP. (Approximate size: 16-inch cylinder, two-foot stroke.) Steam made possible, too, a well-controlled dry kiln. Previously, what drying that was done was done in a primitive kiln in which a charcoal fire was maintained in a pit under the stacked lumber. The fire hazard was awesome. A separate, small boiler and engine powered the gin. Only the grist mill, in the main mill building was subsequently powered by water. It had its own small turbine. The runner and shaft for this turbine, along with the millstones were in the yard of the homeplace about 1954. The millstones were still there in November 1989.

Steam installations like this were common in that day. Hartley Boiler Works in Montgomery made the boilers, and probably supplied the engine.

The boilers were fired with slabs, shavings, some sawdust. What was done with this waste before there were boilers to fire?

Father sometimes fired the boilers, including maintaining the banked fires overnight, when the only load on the boilers was the kiln.

The mill ruins.

Joseph Elmer Rhodes, Sr., stands with his family on the mill dock.

The smokestack for the steam boilers was once heard playing music (1916).

The mill ruins.

Joseph Elmer Rhodes, Sr., stands with his family on the mill dock.

The smokestack for the steam boilers was once heard playing music (1916).

A strange occurrence involved cleaning one, or maybe both boilers at the same time. In any event, a firebox was cold and its door stood open while the crew sat around eating lunch. The sound of a band playing came from the open firebox door! Other men around the mill were called, and men from the commissary came over. This audience listened for what must have been several minutes, and then the music faded away. Someone said it was the Auburn band, that he would recognize it anywhere. And so the notion spread around that the Auburn band was heard playing down the mill smokestack. It was believed that some verification was made, that it was somehow determined that the band was, indeed, playing that piece at that time of day on that date. I expect that everyone thought someone else verified the facts. Twenty-five years later, when some people were beginning to get radios, I heard the story repeated and someone sagely remarked that way back then “someone must have been experimenting.” Experimenting or not, Auburn band playing or not, I cannot account for what is said to have occurred. Could wind blowing across the top of the smokestack have produced a plaintive sound enough like an early gramophone?

Maintenance of this collection of machinery required skills that may have stressed the available supply. An itinerant artisan from New England was welcomed by the management, if only grudgingly accepted by the community. Ed Lawrence turned up with a tent, a kit of tools, a woman, and some children. The community was not certain the woman was his wife. One of the children, a ten or twelve year old girl, was cared for, however, by the local doctor when she was bitten by a copperhead one evening as she walked up the road and hill east of the creek (the gin hill).

The Lawrences lived for awhile in their tent and in “the doctor’s office,” a one-room frame structure on the commissary grounds. There is absolutely no question that the mill management found Ed Lawrence indispensable; the Lawrences subsequently boarded with Grandpa and Grandma in the “home place.” Aunt Bessie remembers Mary Lawrence, the daughter, helping make a bed, when Mary got exasperated at something and bit her!

Lawrence claimed to be an out-of-favor son of the family that founded Lawrence, Massachusetts. Maybe he was. There was no question, however, that he could fix anything in the mill.

Father recalled, one winter morning, finding the lubricator on the steam engine split. A lubricator was a brass oil cup with a sealed lid, mounted on the steam line to the engine, or, sometimes, it was mounted on the steam chest. Two capillaries connected its interior with the steam; one entered the bottom, the other the top of the cup. A needle valve closed one capillary when the engine was not operating, but during operation, steam would enter the lower capillary, condense and enter the cup as a drop of water. This would force a drop of oil out the top capillary into the steam line. Oily steam lubricated the piston.

Water in the lower part of the cup had frozen and split the cup. The mill was down until a replacement could be shipped from Montgomery, or the split one was repaired. Lawrence got his blow torch. Fueled by alcohol, gasoline, or what, I do not know. He asked worried management, whoever was in charge that morning, for a dime. There was showmanship in his style. Then, with the dime, he silver soldered the split in the lubricator.

He could pour Babbitt bearings; he could set planer and molding knives; he could sharpen tools, saws, and molding knives. Local millwrights could do most of these things, too, but none with the élan of Ed Lawrence. I suspect that alignment of machinery, which was becoming more complicated, may have been beyond local mechanics. Ways, or tracks, for the main saw carriage had to be true and perpendicular to the saw arbor, a formidable task without special instruments, but nothing mechanical was beyond Lawrence.

The Lawrences drifted on after a year or so, before Grandpa took his family to Birmingham in 1906. Father recalled mill people wishing he were there when mechanical problems arose.

Father also recalled, as a boy, a suit against the mill for cutting timber on someone else’s land. He recalled Greatgrandfather (who was reputed to be learned in the law) saying, “You boys are going to lose this suit because—. You should have done—.” He neither understood nor remembered why and what. He did recall that the judgment was for some $8000, an enormous amount at that time.

I do not know when the mill ceased to operate. Having to pay the judgment may have helped end the operation, although Daddy did not seem to think so, and Grandpa had enough capital to start in business once he came to Birmingham. Greatgrandfather died in 1901, and Grandpa left for Birmingham in 1906. Uncle Newt and Uncle Dan were then already living in Georgiana; the cornerstone on the building that was their store carries the date, 1906. Uncle Marion had long since moved to Greenville. Only Uncle Jule was left; he did run the grist mill for some time. I do not know if he ran the sawmill after 1906.

Father said they sold out to Forshee & McGowan when most of the timber they had remaining was located where it would have been expensive to harvest. Possibly McGowan was able to run log railroads to get it from the other side more economically. The Rhodes never laid rails, never owned a log locomotive.

Father loved the steam installation, and he took pleasure in talking of it during my childhood and youth. He may have failed to notice that it required much more maintenance and attention than did the water power. Maybe the operation was not viable after steam was installed, especially with most of the timber cut.

From the Mobile Press Register, Jan. 3, 1965

A TOWN VANISHES INTO PAST by Ford Cook

GEORGIANA, Ala. — There probably is not a man alive in this early part of 1965 who recalls, to any great extent, a thriving town to the east of here known as Shell, Ala.

A number most likely can be found, however, who know about Rhodes’ Mill — as the town was more commonly known during its heyday. Today a few mounds of earth, with huge trees growing from them, mark the site of the once thriving town.

At the spot where Alabama Highway 106 crosses Persimmon Creek, about five miles east of here, is where Shell (Rhodes’ Mill) was situated, but to the casual passerby there is no indication of ever having been anything more than heavily timbered lands, as is seen today. A big dam, all but completely gone, has long since deteriorated to the extent that the creek rushes along its way unhampered and where fishermen once angled for the “big ones” in the mill pond now stand large pine and oak trees.

THRIVING TOWN

About a century ago, with the dam holding the waters of the creek to provide power for various activities, Shell was a thriving town with stores, a sawmill, cotton gin, grist mill, a hotel, post office and other business and residential facilities, in addition to the “fisherman’s paradise” in the huge Rhodes’ Mill pond behind the dam. Timber from the surrounding lands furnished the raw materials for the sawmill and as the timbering operations left the lands barren, farmers moved in to till the soil and grow cotton which gave rise to the need for a cotton gin and grist mill.

These three major functions continued to operate a number of years by water power, but then steam became a more practical power for the sawmill and cotton gin. These two industries flourished still more with the installation of steam power and the grist mill grew even larger, adhering to water power.

As more and more farmers moved into the area and timber in the immediate vicinity of the mill became scarce, the grist mill and cotton gin appeared to be taking the upper hand of the industry until the Rhodes Brothers, operators of the mills, put in “log roads” — private railroads — to haul timber from distant points to the mill to keep it going.

SAWMILL CLOSED

With the advent of steam and the new “log roads,” Shell (Rhodes’ Mill) appeared to be on solid footing and continued its upward progress for a few years. Then, almost with unprecedented suddenness, the sawmill ceased to operate. Some say it was because no more timber was available while others say it was because there was no market for the lumber being cut. But, nonetheless, the sawmill did cease to operate, leaving only the cotton gin, which was a seasonal industry, and the grist mill, which by this time had many competitors within its territory.

With the folding of the sawmill Shell began to go rapidly into reverse. Businesses closed, the post office discontinued its service and other facilities ceased operation in rapid order until the town of Shell (Rhodes’ Mill) became a ghost town in almost every respect. Being a seasonal industry, the cotton gin soon ceased to operate, but the grist mill did hold on for a number of years until age and deterioration caused it to discontinue operations.

There are few men around today who can recall, first hand, the flourishing town of Shell, but many do have some recollection of the “old mill pond, the deserted buildings and the grist mill,” that were on the site until about 50 years ago.

Now, as traffic flows swiftly across the modern bridge over Persimmon Creek, only a few feet to the south of the old dam, but few realize they are passing the site of a once flourishing town.

NOTES: The location of the mill is not Highway 106, but County Road 16, roughly parallel and three to five miles south of 106. This road, also paved and graded since WWII, runs southeast out of Georgiana, past the cross-roads of Avant, and on across Persimmon Creek, at the mill site. (See accompanying map.)

Rhodes Brothers did not use a steam log road. W. T. Smith, at Chapman did, however. Only hard-to-get-at virgin timber was left when the Rhodes Brothers sold to “Forshee and McGowan,” I have heard said, about 1906. McGowan owned W. T. Smith, and it is possible that they extended their log roads to get out that timber. If so, they processed it in their own mill. I do not think the sawmill at Shell was operated after the sale. The grist mill, operated by Uncle Jule, did continue, as said above, driven by water power.

From Mobile Press Register, July 4, 1965

INTEREST IN A TOWN THAT DIED By FORD COOK

GEORGIANA, Ala. — It seems that, basically, one of the most popular subjects, taking all phases into consideration, for the reader today is history. Delving into the things of the past, both recent and back into the dim recesses of man’s existence, seems to be a favorite of a number of persons.

Whether these observations be accurate or purely figmentary, an item of history concerning “A Town Vanishes Into Past,” which it was my pleasure to do six months ago, has brought many comments from persons who were themselves seeking information on the former town of Shell, Ala.

The comments and queries, coming from three states — Alabama, Tennessee and Georgia — have been spread over nearly the entire six months since the article appeared, but the most prominent have been from relatives of the men who operated the sawmill, cotton gin and grist mill at the site of the town when it was a flourishing business and industrial center about a century ago.

SOME COMMENTS

To refresh the memory of those who may not recall the item about Shell, Ala, it was a town of “considerable size” located about five miles east of here on Persimmon Creek at the spot where modern Alabama Highway 106 crosses the stream. At that point today, nothing more than a few mounds of earth can be found where once was a gigantic dam to provide waterpower for the industrial operations. Huge trees now are growing where the town was situated until about 50 years ago.

From J. Elmer Rhodes of Birmingham comes the comment: “I am the son of one of the ’Rhodes Brothers’ who operated that mill and I worked in it as a boy. I have many fond memories of my boyhood days in that town.” And from his son, J. Elmer Rhodes, Jr., of Marietta, Ga. comes this comment: “I have, for a number of years, been casually collecting material on that community, on great-grandfather N. M. Rhodes, who founded the mill, and on the engineering that went with the operation. Your remarks agree in all essentials with my data, and I, in hopes of learning more, am curious as to the sources of your story.”

Others were basically ones of reminiscence about the town and others they knew of that were similar as they offered comment on the item about Shell, Ala., or Rhodes’ Mill, as it was more commonly known.

To the younger Rhodes, who sought the source of my information, it can be said: “It is a small world,” because my ancestors settled in that general area nearly 150 years ago and some of them have remained in that part of Butler County since that time. In fact, my birthplace was on a farm less than five miles to the east of that old town’s site, but nothing was left of the town at that time.

NO RECORDED HISTORY

Most of the information concerning Shell (Rhodes’ Mill) was given to me by three persons — my granddad, the late H. B. Cook, who would have been 106 years old now had he lived these last 12 years; my uncle, W. L. Cook, 80, who still resides at the “old home place,” and my dad, E. B. Cook, 73, who spent his boyhood in the area.

Granddad often told of going to the mill, gin and grist mill operated by the Rhodes Brothers as well as many successful fishing trips on the mill pond in his younger days. My dad and uncle can recall much of the town’s activities during its later years, though it had already passed its peak of operation.

Actually, my information on the town was basically a “family affair,” much the same as with the inquiring younger member of the family of the original operators of the town’s business and industrial facilities. So far as my efforts have been able to ascertain, there is little or no recorded history concerning Shell, thus the main part of available information on it must come from those who recall frist hand or were told by those who did see it in operation.

To those who took the time to offer comments and make inquiries concerning the town of Shell, Ala., let us say, “It is appreciated.”

NOTES: I noted two headstones in the “Riley Cemetery”, probably in 1968. Both close to Greatgrandfather’s grave, I believe. On one: H. B. Cook 1858-1952. The other was for his wife, Florence, 1866-1901. Aunt Ethel said, ” Henry Cook was Cousin Ellen’s brother; his wife was Florence; their children were Willie, Roxie and Lena”. There is a good chance that Henry is H. B., Ford’s granddad, and that Willie is Ford’s uncle, W. L.

Cousin Ellen was Jeff Hudson’s wife. I knew her in Montgomery when I was a child. Her son, Jeff, older than I, runs an office supply store in Dothan, Ala.