The life of Newton Marion Rhodes (1829–1901)

He was named for two Revolutionary War heroes. In his early twenties he named his second son for one of them, and at forty named another son for the other.

When Newton Marion Rhodes was born in 1829 practical communications and travel went at the speed of a horse. Railroads went everywhere in the country in 1901 when he died. Telegraph lines paralleled the railroads. A private telephone line ran from his mill office to his home about a mile away. Is there more trauma from change across my lifetime than across his?

Newton Marion Rhodes, my greatgrandfather, materialized in South Alabama. No one knows of his forebears. (Not precisely; his father, also Newton Marion, is in the 1830 Census for Butler County. His mother was Amy.) Vague tradition says the family came from Virginia or South Carolina—not unlikely places. His father died when he was a small child, four years old, say. We do not have details of how the family made out until he and his sisters were young adults. Instead of details we have one vignette.

When he was still a child, he was trying to plow corn with a mule, but with clumsy, unsatisfactory results. The mule was tangling his lines and young Greatgrandfather thought the mule was being uncooperative. Finally the child was reduced to tears. A watching neighbor then advised him that the mule knew better how to plow corn than he did, that he should plow the other side of the row.

Everyone who had known him laughed hard when this story was told, and it was told many times. The notion of comparing his know-how with that of a mule was preposterous, that a mule knew better was hilarious.

I am not a mule-man either, but corn was plowed with a sweep blade mounted on a Georgia plowstock to clear weeds by cutting them off just under the surface, and to throw dirt up around the stalks when they had grown tall and the ears were making. Mules must have been accustomed to always going down the row with the near corn always on the same side, the left I believe.

When Greatgrandfather was still a young man he established a “plantation.” It consisted of a large log house, noted on the community map, and some surrounding land. I do not know if any slave labor was employed, but it is possible as there are lots of black people in the area. The farm must have been successful, as Greatgrandfather was a respected citizen in the community in his mid-twenties when he became Justice of the Peace for South Butler County.

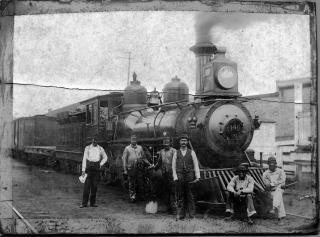

Greatgrandfather helped raise Jeff Hudson, seen here (second from the left) with his oil can and locomotive in Greenville, Alabama (1896).

Greatgrandfather helped raise Jeff Hudson, seen here (second from the left) with his oil can and locomotive in Greenville, Alabama (1896).

JP Court was held in Hudson’s store, a mile from the log house and half a mile from where Rhodes’ Mill would flourish. One of Greatgrandfather’s sisters married a Hudson. When her husband died, Greatgrandfather became unofficial father to her sons, one of whom, Jeff, became an engineer on the L&N. His picture (dated 1896) with his engine and train crew stands today in my study. I got to know Jeff’s widow when I was a child. She was a Cook. Her brother, Henry (H. B.) and his wife Florence are buried close to Greatgrandfather in Riley Cemetery.

Greatgrandfather held the post of JP some ten years, at least. I have read the docket for those years, and there are no entries for about eighteen months, when he must have been away at the Civil War. Family tradition says he was taken prisoner early in the war, and was imprisoned on Ship Island (Fort Massachusetts off Biloxi and Gulfport) for the duration. The docket suggests a shorter service, but the imprisonment was real. (The docket was loaned to me in 1954 by Olive Rhodes Page, Uncle Jule’s daughter. I read parts of it into a tape recorder, but the tape deuterated, and only fragments of it can be understood on a copy. I returned the docket to Olive in the summer of 1955.)

Greatgrandfather was not a talking Confederate veteran. He regarded the war as a sad and troublesome time. He did occasionally tell of hunger in the prison camp. He was often feeling so unwell that he passed up his share of what was available. For humiliation, the prisoners were guarded by colored soldiers. There was enough brutality to make a thoughtful man reticent.

As noted, the plantation or farm was successful. One account says it once employed “fifty plows.” This seems exaggerated.

Greatgrandfather styled himself “cabnet maker” (sic) in the 1860 Census, and it reports he had $12,000 worth of personal property, a considerable amount. Had he established a cabinet shop, possibly at the future mill site? Did it include powered machinery? There is no family tradition that says so, but there is a tradition that he made furniture as a hobby.

It was after the Civil War, probably, when the mill was built and some seven thousand acres of timber acquired. Where did the capital for this come from? From the earnings of a successful farm or cabinet shop? Unlikely. Maybe it started with much smaller holdings, and grew as the operation became successful.

In any event, Rhodes’ Mill, as the operation and the community around it became known, did get established. A large mill pond was dammed up. It supplied water power for many years, and the pond served to float big logs to the mill, sometimes from sites several miles away. The mill pond was also a source of recreation. Neighbors fished there; people from further away fished and camped on the commissary grounds.

The commissary yard was favored by picnicers and campers for years after the mill closed. Earl McGowan of Chapman wrote me that he swam in the mill pond as a boy, 1912–1914 I guess. About 1929 I went with my father in his 1928 Chevrolet coupe to Butler County. Because of road work along Highway 31, we took the road to Luverne from Montgomery, and came to the mill site from the east in the early evening. There was a full moon. We had talked of camping out ourselves, but the commissary yard was full of revelers who had come out for the evening, or maybe to camp overnight. We drove off the road on the north side of the road, into the woods, but found no suitable area to spend the night. After half an hour we drove into Georgiana, and spent the night with Uncle Newt.

A boarding house in the community served as an informal hotel for the more affluent. Milton Smith, president of the L&N Railroad must have come. Father paddled a boat for him.

A fish trap at a flood gate would yield fish galore when the gate was opened to lower the pond for repairs, to pass the spring rains, or for other reasons. One colored man, George Trawick, made his living fishing. He was so honored in the community that he was buried in what was normally white burial grounds, the same where Greatgrandfather rests today.

The mill and Greatgrandfather are so entwined that one’s story cannot be told without the other. Greatgrandfather’s offspring affected the enterprise, so they need to be enumerated and identified.

Greatgrandfather married Elizabeth Stewart, and their firstborn was Robert William, in 1850, when Greatgrandfather was twenty-one. Robert died in his mid-twenties, so his impact on the operation was minimal. There is a touching four-line verse on his headstone, composed by Greatgrandfather, I am sure. There were two more sons, Francis Marion (b. 1852) and Julius Wood (b. 1854). Their mother died in 1856.

How Greatgrandfather managed three small children for the next three years is left to the imagination. His mother, Amy, still lived; maybe she helped. (Greatgrandfather wrote a verse for her tombstone in 1868. Brandon and I could make out only the first line or two.) Then he married my greatgrandmother, Sarah Turner, in 1859. Daughter Elizabeth was born in 1860; an “infant” daughter died in 1863. Their sons were born after the Civil War. Twins, Dan and Dave, 1866; my grandfather, Joseph Turner, 1868; Newton T. (Uncle Newt, whom I knew), 1870; and daughter, Sarah Della, 1873.

Daughter Elizabeth married Wade F. Shell in 1880. Uncle Wade and Uncle Marion must have run the store or commissary. Rhodes Mill became enough of a community that a post office seemed appropriate. Uncle Wade filled out and signed the application, and became the first postmaster. The post office charter, due to a lapse on the part of a government clerk, named the community Shell, rather than Rhodes Mill, the popular name of the settlement. No correction was sought, and a road intersection just up the hill from the mill and commissary sites is marked Shell on maps today. The Shell family lived in the area, but it was that clerk’s mistake that put them on the map.

Uncle Wade and Uncle Marion did not stay in the community. Subsequently they had a store in Greenville, the county seat of Butler County, some twenty miles away.

Uncle Marion’s first wife, a Graham, died. His second, called Aunt Callie by my aunts, was kin to the Beelands, the name of a third partner in the Greenville store. (We knew a Beeland offspring in Cobb County some years ago. Beeland’s store closed during our association.)

A son, Grady, emigrated with the Graham family to Texas, and he was later jailed in a shooting. No details. Son, Randall, also moved to Texas or Oklahoma. Son, Stacy, was injured running timber, and subsequently ran a pool room in Tampa.

Uncle Wade left the partnership and went to Birmingham after Grandpa moved there (1906). His wife had died, and he had a daughter, Alva, to care for. He and Alva boarded with Grandpa in Birmingham until he remarried.

Uncle Jule officially ran the grist mill, but he helped manage the sawmill, too.

The second group of sons, nominally ten years younger, took up functions in the enterprise, too. My grandfather, Joseph Turner, managed the sawmill, and also acquired a mill of his own at Avant, three miles from Rhodes Mill, along the road to Georgiana. Dan managed the “lower mill,” maybe he owned it, a mile and a half downstream from Rhodes Mill in Persimmon Creek Swamp. He and his twin, Dave, managed the store or commissary after Uncle Marion and Uncle Wade went to Greenville.

Later, maybe after the mill closed, Dan and Newt ran a store in Georgiana. Dan became mayor and Newt had a cotton brokerage office across the alley behind the store.

Dave makes colorful copy, but his life was tragic for his family. He always wanted to appear more than he was.

Along the road where Grandpa and his family lived was “Uncle Dave’s big house” in the fork where the road to the Riley Cemetery (and in that day, the school house and the Baptist church). Across the road was “Uncle Dave’s buggy house.” The house was probably not ostentatious by subdivision standards, but for the community it was described as “big.”

He took over buying for the commissary, and maybe for the mill, too. Was clerking and selling too mundane? This took him often to Montgomery, and it was rumored that he kept a woman there. I am sure the rumor gave him more pleasure than the woman, if, indeed, there was one. He speculated in some property or enterprise on the Isle of Pines, south of Cuba. Some kind of plantation, maybe. He would go off to visit the property for weeks at a time.

Dave’s wife, Mattie Shell (another Shell-Rhodes match), was sickly. She may have had pellagra.

Then, sometime around 1900 or 1902 Dave disappeared. He did not return from one of his trips. Grandpa hired Burns Detective Agency to try to locate him, but nothing came of it. Years later someone told my father that he had died in Arizona, but this was never confirmed.

Had a speculation gone so badly that he could not face his ruin in the community? Or had he been murdered on the road to Georgiana because his sporty clothes suggested that he carried gold? He would have liked people to think he did. His body could have been dragged into the virgin forest and never found. His end may never be known, but there is no uncertainty that his son, Hubbard, had to quit school and go to work. Hubbard was my father’s boyhood companion. In the twenties Hubbard worked in Uncle Dan’s store in Georgiana, and later, after the store closed, at Sims Hardware Store.

Aunt Bessie says Dave’s son was Herbert, and undoubtedly she is correct. That name is on his tombstone in Georgiana. I leave it Hubbard above to recall my father’s habit of slurring and modifying some words. When telling of Herbert and when talking to him, Hubbard is the word that came out.

Aunt Bessie also recalls it was Pensacola where Dave went to buy. Pensacola seems a likely place to jump off to the Isle of Pines, and maybe lots of buying was done there. Certainly timber was sold there. The mill also had ties to Montgomery; witness the purchase of tie rods there for the church in what follows, and the boilers coming from there. Which town does not matter to this story.

By the eighteen-nineties the sons were doing the everyday running of the several enterprises: the sawmill, the grist mill, the commissary, the cotton gin. Greatgrandfather came to spend more and more time in his office on the hill above the mill pond. More on this after a few items about his immediate family.

Sarah Turner Rhodes died in 1883. Greatgrandfather married a third wife. For years I did not know her name, nor the date, but I had the impression she was there when my grandfather was in his teens, in the eighteen-eighties. Recently David and his family found in the Butler County Records that she was Matti Amos (possibly her married name, if she was a widow), age 45, and the date was 1885 when they married. Also, I think she was from Greenville, a town lady, if not a city lady. She was sent back to Greenville after a short time, two, three years, I do not know. Greatgrandfather’s family Bible, which I have, and other scraps in writing of his are completely silent about her.

Greatgrandfather was a circumspect and devout man who never used profanity. Never? Well, when he was locking this lady’s trunk to send her off he is said to have mashed his hand or finger or thumb in the trunk lock. With that he exploded: “Dad gummit, Woman, I’ve had nothing but trouble since you came!”

The sons grew up and established their own homesteads. Grandpa established his on the road above Persimmon Creek Swamp 0.6 miles from where it dead-ends into the road up gin hill from the mill. A quarter mile farther south was Greatgrandfather’s log house. Uncle Newt had a four-room house across the road.

Greatgrandfather needed a housekeeper. Some acquaintance told him of a lady in Mississippi with three little girls whose husband had died (killed on the railroad?). Lura Beasley Young came as his housekeeper sometime in the early nineties. By all accounts she was a strong, conscientious, able lady. My grandmother was grateful to her for her assistance and support as Grandma raised her babies and small children. Miss Lura would take her children and my aunts and uncle and my father swimming in the creek beside the commissary. At some time, Greatgrandfather and Miss Lura moved into Uncle Newt’s house, just across the road from Grandma and Grandpa. (Uncle Newt must have, by then, moved to Georgiana.)

The arrangement was going swimmingly when Uncle Jule’s wife began saying through tight lips how scandalous it was for Papa to have that young widow in his house! Her daughters Pearl and Olive repeated their mother’s opinions. They were just little girls. They would have been amusingly ridiculous had they not spread heartache.

Miss Lura would not tolerate such. She confronted Greatgrandfather, saying that if people were going to talk, then she would leave. He then asked her to marry him. She did in 1895. She was thirty one. Greatgrandfather was sixty six. Was he railroaded? Did he get what he wanted, anyway? Should we feel sorry for the old man? Or should we rejoice for his fortune?

Greatgrandfather moved most of his life in a few square miles about the mill. The Civil War took him a few hundreds of miles away, and he must have gone to Greenville many times. But I see him moving mainly in an area bounded by Wesley Chapel Church, the mill, and his home.

In his old age, he would mount his horse, Bill, and ride to his office on the hill above the mill pond. Someone probably saddled Bill for him. On cold days a mill hand would bring split blocks of timber to fire the stove.

When something big enough was up, he would stroll down to the mill to size up a mechanical task. In 1897 he strolled down to be photographed, with Uncle Jule and some six or eight men from the mill, on the dock where logs were rolled after being drawn up from the pond. The photographer set up either on the pond bank, and shot the mill and the men across part of the pond, or else the floating wharf—which was usually fast at the bottom of the log ramp—was floated out into the pond for him and his camera. The latter is more likely; the floating wharf is not to be seen in the photograph.

It was not very cold when the picture was taken. Some men were in coats, others in shirtsleeves, but Greatgrandfather has his hat on and a cape around his shoulders, as befitted an old man.

That could have been the day and the same photographer who showed him sitting in a chair, wearing a frock coat, and with a try square in his hands. I have this picture, too.

Why the try square? Maybe he was using it when interrupted by the photographer, and maybe it would remind all who looked that he had a hobby of building furniture, and had once been a cabinet maker. A table in Wesley Chapel was shown to me that he had made. Its top was twenty by thirty inches. It had straight legs, sturdy, bordering on heavy, serviceable rather than graceful. It had recently been refinished when I saw it. The yellow pine was beautiful. Did he build furniture at his office, at home, or where?

Surely he strolled down from the office and out to the flood gates the spring day that the gates were opened, and a huge loggerhead turtle washed in and jammed, preventing the gates being closed until he was removed. Father recalled that when teased with a stick, the turtle would snap a one-by-two in half.

The open gates nearly carried a boat of fishermen over the dam (or levy), too. One of three fishermen was Hugh Hall, Sr.’s, father. (This was B. J. Hall, married to Fannie Shell, Uncle Wade’s sister. He died a young man, 27, say. There was much speculation about his name; he always used initials, only. Some said it was Bar Jonah, imposing enough. R. Hugh Hall, Jr. recently found his grandfather’s name on his father’s birth certificate. Not imposing at all: Bill Jones!)

In his office on the hill Greatgrandfather would also be available for advice when one of his sons needed it to manage the mill. Father, as a child, would sometimes go see him there and come away with a dime. In between relatively infrequent interruptions he read, and he wrote poetry!

How did he know there was such a thing? His schooling must have been minimal, and he had no library to speak of. His grandchildren remembered his Bible and a big dictionary, both of which he read often and long. That is all, besides newspapers and magazines.

On January 12, 1886, just over a century ago, the mill pond was frozen over. He assembled some verses that recited several often-expressed sentiments. First he described the sunlight on the ice, and then he contemplated the quiet mill, probably closed because of the weather. The mill was the centerpiece of his worldly success, which was considerable.

He called on his offspring to hold the land and keep the mill running. “From the mill the hungry feed” in today’s idiom would be maintain the jobs and nourish the community.

It was not a polished poem, but there may not have been another poem attempted that month in all the state between Mobile and Montgomery. None of his other verses are polished, either, but they are as good as mine. The subjects were homely notions that moved him. He had the urge to write them down.

On a scrap of paper preserved with the poem, “The Water Mill”, he expressed what all of us with that urge experience. I do not know whether it was meant to be poetry or prose, but it contained, “when trying [to express] that [which] we and we alone know—then we feel at a loss.”

His sons did not keep the mill. The admonition in “The Water Mill” was a sentimental whimsy while he sat in the warm office watching the ice down on the mill pond. In that comfort it may have seemed that he had built something that would work forever, forever bringing income and satisfaction to its owners and its workers.

Each of us would like to think that his creation will work forever. But we know its life is limited, whatever it is. Poets know it, and Greatgrandfather knew it.

He did, in one line, say “improve the mill,” but offspring need more latitude than that. He did not mean hold it at all costs, once his reverie passed.

Greatgrandfather was lean, almost gaunt, medium height, with a full beard cut square across his chest. Son, Julius, was similarly built, and maybe son, Dan. My grandfather, Joseph Turner, and Uncle Newt tended to be rotund once they became slightly sedentary.

Greatgrandfather supported the Methodist Church. Wesley Chapel Church was built with lumber from his mill. The church is a frame structure, and the builders gave no thought to thrust from the forty-five degree roof on the long side walls until the walls began to fail. The solution was not flying buttresses, as in previous church design failures. Rather, wrought-iron tie rods, with turnbuckles, were ordered from Montgomery. They are to be seen in the church today. My father drove a team and wagon to Georgiana to get them from the railroad freight or express house.

Greatgrandfather supported the Masonic Order. The Masonic Lodge was on the hilltop above the mill, the same hilltop where his office was. The marble slab over his grave has a large Masonic symbol, the compass, and the big G carved on it.

His obituary, in the Greenville paper, was a little flowery, as obituaries were in that day, but it was an earnest statement by the editor that Greatgrandfather had been a man of integrity and an asset to the community.

MR. NEWTON M. RHODES DEAD

On last Wednesday afternoon at his home at Shell, this county, Mr. Newton M. Rhodes passed away. He had been feeble for some days, but just before his death he seemed better and was up at the mill. During the day he was taken suddenly ill and the thread of life gave way. He was about 73 years of age and a native of this county. For the past thirty years the deceased has been engaged in the lumber business in the southern part of the county. Eighteen or twenty years ago he took several of his sons as partners in the business.

Butler county has never had but few, if any, better men than the subject of this notice. While he never amassed a large fortune he was ever in comfortable circumstances, and never turned a stranger from his door. The writer of this article has known Mr. Rhodes for more than thirty years and never knew anything but good of him. He leaves a number of children among whom are Mrs. W. F. Shell and Mr. Marion Rhodes of this city. Two are living in Georgiana, one his youngest, Mrs. A. N. Parker lives in Montgomery, and others are conducting the business of the Rhodes Mill and Mercantile Co., at Shell.

The deceased was buried at the family burial ground near his residence, with the Masonic service, of which order he had long been a member. He was also a consistent member of the Methodist church. Rev. Mr. Sanders, his pastor, officiated with his Masonic brethren at the funeral. A very large number of relatives and friends were present.

The Advocate regrets to chronicle the death of such citizens and extends sympathy to the many—